November 3, 2023 – The dishes at Wahpepah Kitchen are a mouthful for those unfamiliar with the Kiikaapoa/Kickapoo language.

Take the peesekithi-a, miisiikwaa nepoopii and peekipaateeki mehsweeha, to name a few. (That’s charred deer sticks, bison stew with wild onions and Ozette potatoes, and smoked rabbit blue corn tamales.)

They are also colorful, vibrant, thoughtful, fascinating and habit-forming.

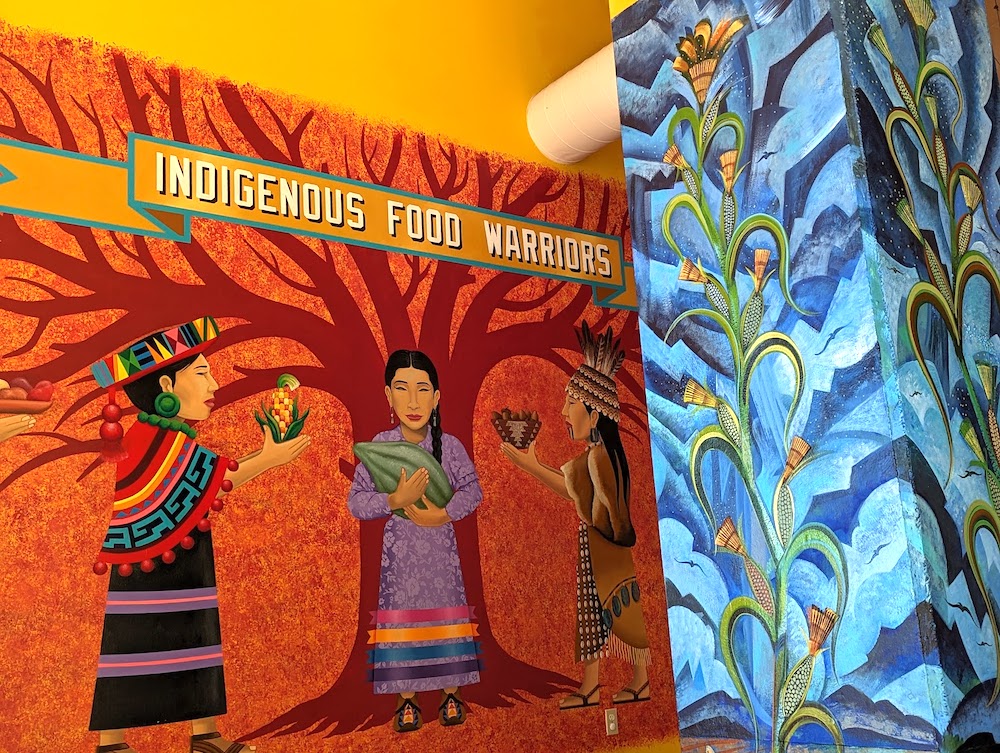

Above them on the wall appears a mission statement, which reads (in part): “Wahpepah’s Kitchen aims to use Indigenous knowledge and expertise to transform food systems so they honor the origins, land and Indigenous connection to each ingredient.”

I tried the ihskopihpeniiya peeskoneiihi (sweet potato hibiscus) taquitos, pahteewi chaaskisii (smoked salmon) salad and a mixed-berry frybread with miinaki peeskoneiihi (elderberry hibiscus) tea.

They went fast. And would’ve gone faster if they didn’t inspire cause to pause. In between bites, thoughts turned to additional things these dishes—and food in general—access, like identity, history and memory.

I asked a Wahpepah staffer, given the cancellation of the 2023 season, where they procure the salmon. The answer made sense: from the Lummi Nation natives of the far reaches of the Pacific Northwest, who have protected rights to fish West Coast waters.

That took me two places: 1) back to a summer rally on the steps of Sacramento’s capitol building; 2) a discussion with Valentin Lopez, longtime chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band native to the Pajaro River Basin and surrounding region.

On July 5 In Sacramento, an unprecedented number of tribal representatives, commercial fishermen, and conservationists called for stronger laws to care for the rivers and salmon upon which tribes and ecosystems depend.

Sierra Club California director Brandon Dawson joined the throng. “It’s good to bring together people that have been marginalized,” he said.

The talk with Lopez came while researching a story for Monterey Bay Fisheries Trust about the region’s first fisherfolk.

“We have to respect and love [native seafood species],” he said. “We look at fish as a relative, with the same Father Creator and the same Mother Earth. We have a responsibility to them. We have to pray for them, sing for them, create relationships and listen…and not view them as a commodity, not solely as a resource that needs to be dominated or domesticated.”

I asked him how food might help humans connect with Indigenous traditions. After all, not many contemporary Californians pay attention to fisheries and river management. Or are versed in native history—in large part because so much has been erased.

But plenty of them like to eat good food.

He acknowledged food is powerful, but not necessarily in an uplifting way. He pointed out that for three waves of colonizers (the Spanish, Mexican and American), subjugation went beyond religion and land.

“Part of that domination meant converting food diets, converting food sources,” he said. “Our people had all these food plants—including eight types of Indian potatoes knocked out by grazing cattle—that nobody knows about.”

Wahpehpah occupies a spot right next to Fruitvale BART Station in Oakland. That’s a convenient location in many ways, but a trek from Monterey Bay.

But there’s good news on that front, made a touch more timely by last month’s Indigenous Peoples’ Day (Oct. 9) and Native American Heritage Month (November).

Christina Lonewolf Martinez will be an enthusiastic part of that. She’s a local chef who’s apprenticed at Sierra Mar in Big Sur and helped open Cella and Stokes Adobe in Monterey.

She’s also a proud Comanche and Apache descendent, and a new mom—who is taking time amid maternity leave to reflect on what she feeds her infant and on launching an Indigenous ingredient farmers market stall. (Items she’s considering include things like bison burgers on acorn buns and blue corn tortilla tacos.)

For her, food allows her to remember, re-energize and re-educate, starting with her nieces and nephews, who think tomatoes, potatoes and chocolate are Italian, Irish and French cultivars, respectively. (Hint: They’re not.)

“I want to reclaim the identity of those ingredients as Indigenous,” she says. “They’re actually from [the Americas] and have been here for thousands of years. That’s why I’m dead set on re-Americanizing American food into Indigenous food.”

Lonewolf Martinez will participate in Nov. 19’s Esselen Tribe of Monterey County Harvest Festival fundraiser at Hacienda Hay & Feed in Carmel Valley. For the event she’s planning wild turkey and acorn dumpling stew with morels and chanterelles.

That gathering—laden with art, crafts, music, movement, and meals—comes in concert with many other opportunities from a range of area groups and collaborations.

The multifaceted exhibit Contemporary Indigenous Voices of California’s South Coast Range is now up at the de Young museum in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. Nov. 4 it hosts three hours of free programming (11am-2:15pm) featuring basketry demonstration, panels with artists, cultural leaders, and elders from several Bay Area tribal groups down through the Santa Cruz Mountains, Monterey Bay and Salinas Valley.

Meanwhile the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band provides a number of ongoing activities for the public. Monthly work days at Pie Ranch and San Juan Bautista State Historic Park stand ready for volunteer participation.

The Amah Mutsun Land Trust has also partnered with Sempervirens Fund, California Nativescapes and members of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe to plant the The Mutsun Gardens at the Robert C. Kirkwood entrance to Castle Rock State Park. Bursting with 60 native species, the gardens welcome visitors sunrise to sunset.

(Central Coast citizens can also follow and reinforce the effort to protect sacred Juristac grounds from development as a gravel quarry.)

Then there’s perhaps the most accessible way for anyone to sit with what food means to anyone else: Take a second and think.

New mom Lonewolf Martinez—“We’re more of a pack now,” she concedes—elaborates.

“Almost every emotion can involve food,” she says. “It’s a day by day thing, and learning to prepare and experience it with more mindfulness makes it more of a loving thing—and makes passing it on so important.”

More on the Esselen Tribe of Monterey County’s Autumn Harvest Fundraiser via its EventBrite page.

About the author

Mark C. Anderson, Edible Monterey Bay's managing editor, appears on "Friday Found Treasures" via KRML 94.7 every week, a little after 12pm noon. Reach him via mark@ediblemontereybay.com.

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/