September 27, 2022 – Most Americans can recall a scary school cafeteria situation.

Maybe it involves mystery meat. Or ghostly canned vegetables. Or Joes so gruesome Sloppy would be a compliment.

For a group of local parents with kids in the Salinas City Elementary School District, the school food situation wasn’t so much scary as it was horrifying.

So they got moving on a solution that as of this month is as real as it is appetizing.

Megan Bailey, herself an instructional chef at Cabrillo Community College’s culinary school in Aptos, is one of those parents, with a fourth grader and kindergartener at Lincoln Elementary School.

Pre-COVID she always sent her oldest to school with his own lunch because she knew the campus offerings weren’t ideal. But when the pandemic came to town and food pickups were offered, she figured walking to the nearby school for lunch would be a fun excuse to get out of the house.

Then she witnessed sandwiches with super processed ham and cheese-flavored cheese on sugary white bread paired with canned green beans. She saw her boys bring home plastic-packaged taco-empanada pockets—“taconadas”—premade somewhere and designed to be reheated in said plastic. She observed summer camp breakfasts composed of a cinnamon graham cracker, raisins and a juice—as she says, “all sugar.”

Unbeknownst to Bailey, similar frustrations with preservatives and processing—and desires to nourish differently—were surfacing at a district leadership level, among other parents and in school food service circles.

A district trustee field trip to a smart-cheffing school revealed better eating was attainable, and inspired the formation of a nutrition working group. Superintendent Dr. Rebeca Andrade reinstated a district wellness committee similarly composed of staff, parents and teachers. East Salinas advocacy nonprofit Building Healthy Communities helped parents and food service staff find common ground.

That led to an awakening, as district director of communications and community engagement Mary Duan observes.

“There was a realization that this is bigger than, ‘Let’s get more fruits and vegetables in the kitchen.’ It was on the scale of: ‘We need to remake our kitchens and systems,’ to find the type of assistance that says, ‘Here’s how to instruct your team to make soup for 7,000 kids.’”

With recommendations in hand from the wellness committee, SCESD food services manager Christina Varela sent out RFPs to a handful of promising organizations with experience bringing real food to young bellies.

One happened to be a Chicago-based B Corporation called Beyond Green, which appeared on the wellness committee’s radar because it helped revolutionize nutrition at Greenfield Unified in South Monterey County.

After selecting Beyond Green, its founder Greg Christian appeared at the trustees’ July meeting, where he proposed a 3-year, three-phase plan including cook training, menu development, ingredient sourcing, equipment upgrades, and the build-out of a large, central and shared commissary kitchen.

A month later, Christian returned to meet with parents.

His opening message to the assembled audience at district headquarters on Main Street, in not so many words, was this: I don’t know jack about Salinas.

“I’m not from this area,” he says. “I’m very ignorant, so I have questions to help me learn more.”

What he does know, however, is how the U.S. school food system broke.

He can recount how massive food service companies approached schools in the 1970s with a tantalizing offer: Us big boys know efficiencies in this industry educators need not bother with. You can slash staff. You can rip out your cooking equipment. You can simply reheat.

“Almost everybody bit,” Christian says. “Cooks no longer cooked.”

He also knows how to remedy those ills, even if he isn’t familiar with the community’s specifics.That’s because he’s spent 15 years developing local responses to a national problem, from schools in Buffalo—where the entire group of seventh grade girls stopped eating in protest—to a high school in Illinois, where 1,200 students signed a petition to change the food.

Which is also why he knows one of the first—and fundamental—steps to creating major progress is familiarizing himself with the specifics of a new place. Illinois, per Christian, imports 96 percent of its food. The Salinas Valley not so much.

“Every project we’ve ever done looks different,” he says. “Some basics are the same—measuring plate waste, looking at overproduction, finding efficiencies to buy fresh, local food. And every menu looks different, and the dreams look different, but the main dream in the end is when kids leave eighth grade, they crave nutrient dense foods.”

Another basic but beautifully simple first step: Measure the milk.

Scales are the quickest tool to come out, and at every campus leaders are shocked how much money is poured down the drain. At the Greenfield schools they were pacing $50,000 a year just in milk kids threw in the trash.

As Beyond Green weighs and identifies what’s being wasted, they capture savings that can be applied to buying and building out the infrastructure for local food.

“School kitchens are run like Thanksgiving, only no one eats the leftovers,” he says. “The money to buy fresher, more local food, and the time to cook, is in the system, only people in the system can’t see it at first.”

Beyond Green made the RFP cut partly because of its attention to sustainable practices like composting. “At Beyond Green we haven’t bought a garbage bag in 15 years,” Christian says.

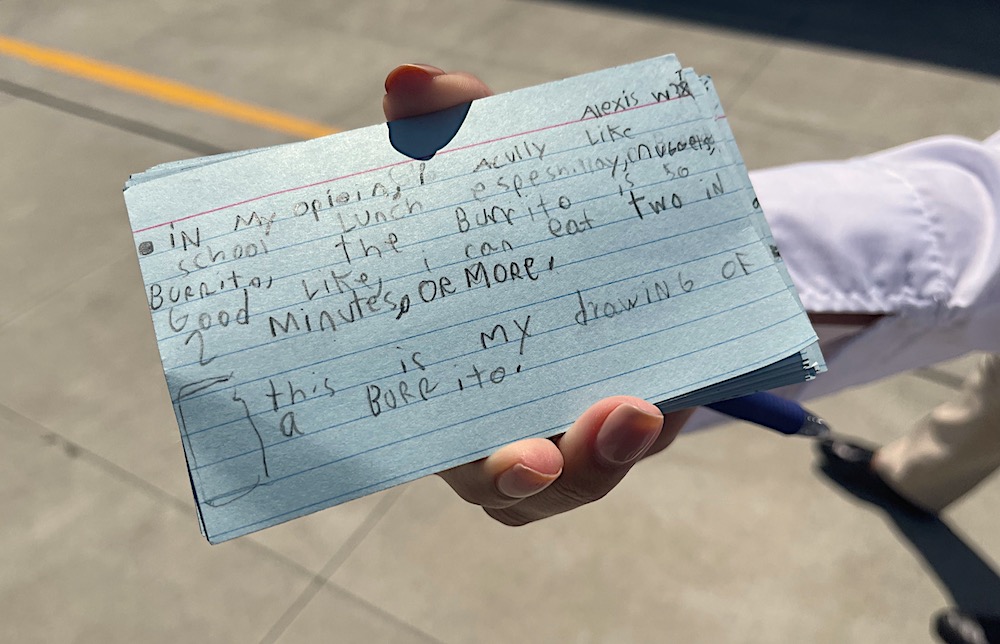

The SEUSD parents—as with the wellness committee, all moms—didn’t skimp on feedback.

One home vegetarian gardener/chef described how her young son doesn’t recognize the meals served as food and refuses to eat it. Another described how much the diet depends on bland cold cut sandwiches and pizza.

A teacher who is also a mother reported, “I can teach all I want but it won’t matter if they’re not capable of learning because they aren’t fed.” Many asked how they could help. One admitted she was shaking with anger just talking about it, saying, “It is hard to be patient when kids aren’t getting good food.”

“I get it,” Christian said. “Food is emotional.”

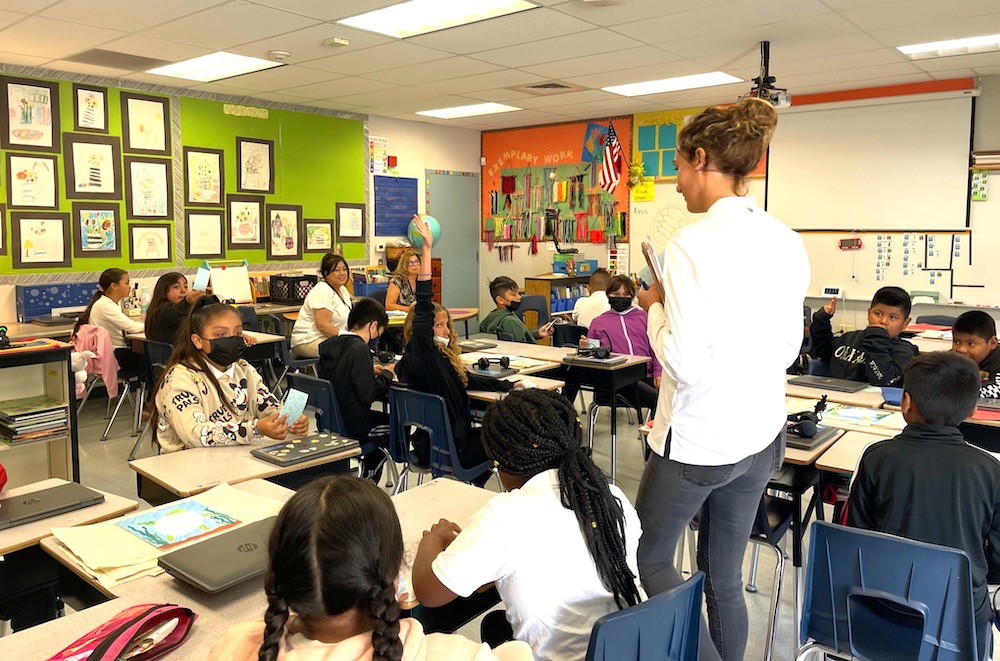

Before meeting with the parents, Christian and his team also visited eight district cafeterias, talked to 300 students, 26 workers, looked at purchasing and checked SEUSD’s organizational chart.

As he told the parents, “What we found was what we see all over this all over the United States.”

The good news for the understandably impatient parents: Last week the SEUSD trustees voted “yes” to bring in Beyond Green. The vote was unanimous.

Back at the parent meeting, Christian took pains to tell Edible that this isn’t some rosy and hopeful mission. The numbers have to click as much as the sourcing and student satisfaction.

“How do you serve fabulous food to make money in a way the customer calls again—but you’re also serving the planet and people?” he asks.

A look at the menus he brought with him from the Chicago kitchen he calls “our learning lab” sound fabulous, whether compared to what I’ve seen served in schools or in restaurants: Greek turkey meatballs with pita and cucumber, butternut squash-white bean-pasta casserole, chicken-and-sweet-potato fritters, 250 items all told.

After the vote, Christian tells me his team is ready to roll to Salinas once they get the go ahead, with the stakes of what they do very much front of mind and appetite.

“How do you do what you want to do with every plate?” he says. “This is not easy…and we can’t fall down, because this is not some crazy experiment. It’s kids’ health.”

More at Salinas City Elementary School District’s newsroom page.

About the author

Mark C. Anderson, Edible Monterey Bay's managing editor, appears on "Friday Found Treasures" via KRML 94.7 every week, a little after 12pm noon. Reach him via mark@ediblemontereybay.com.

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/