March 29, 2021 – One of the major keynotes at EcoFarm 2022 came with an ambitious—and optimistic—title: “The 21st Century Food System We Deserve.”

Such an aim made me skeptical. After all, our food system is one wherein its flaws are difficult to overstate.

Billions of tax dollars go into the agribusiness sector, but millions of Americans don’t have access to healthy food. Industrial agriculture degrades the environment, accelerates climate change and pushes out smaller farm owners. Workers in the food industry often face substandard labor conditions and frequently can’t easily obtain the food they harvest. Farm animals suffer. As a nation we waste vast amounts of food, but a swath of society goes hungry.

Fixing that with an hour-long talk felt unlikely.

But I emerged from the presentation hopeful.

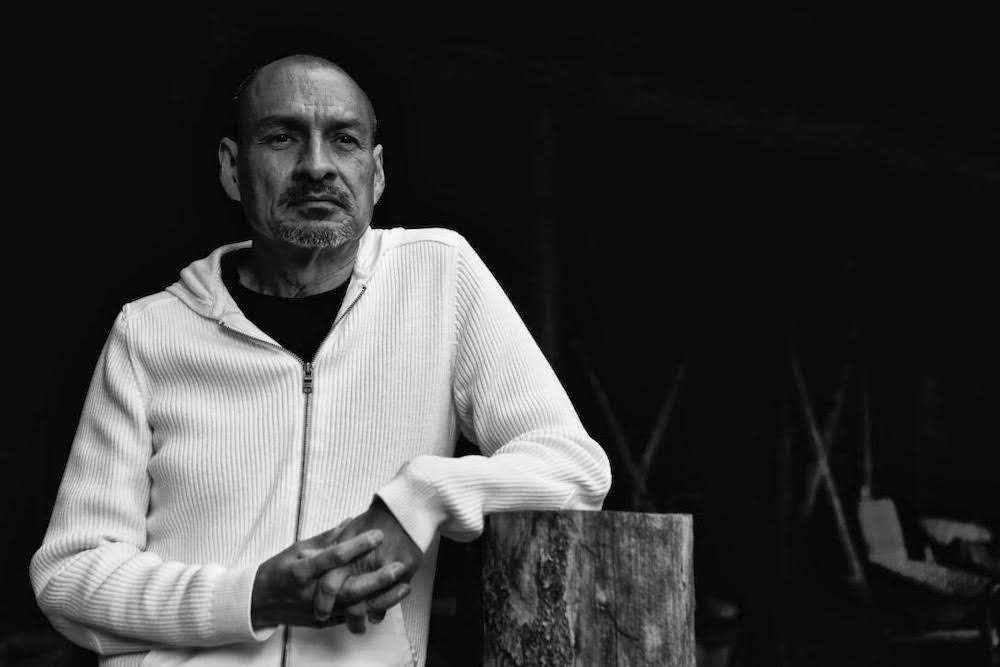

Such was the power of Ricardo Salvador’s outline for a just and functional update to the U.S.’s way of feeding its people.

Salvador is a senior scientist and director of the Food and Environment Program for the Union of Concerned Scientists. The woman who introduced him provided a hint at the insight he would reveal.

Alexa Delwiche of the Center for Good Food Purchasing in Berkeley has been working to improve access to healthy food for decades. She told the virtual audience that, despite her years-long efforts in that field, her dad never really understood what she did or why she dedicated herself to that pursuit.

But that changed when he read a piece by Salvador and former New York Times columnist Mark Bittman titled “Goodbye, U.S.D.A., Hello Department of Food and Well-Being.”

“In 1,000 words or less,” she said, “[Salvador] communicated ideas I’d been trying to explain to my family for 20 years.”

If you go no further in this piece, reading through that op-ed is an outstanding 10-minute investment of time.

In that story and in his talk, Salvador takes a complicated problem and provides clear-eyed solutions.

Edible Monterey Bay reached him at his home in Maryland—not far from his K Street office in Washington D.C., where he’s within walking distance of many lawmakers he pushes toward fairer food policy—to talk about the possibilities he emphasized in his EcoFarm presentation.

“These are the major areas [for] structural reform,” he says. “That’s the positive take, anyway: the vision of what we can have. The flip side is that they’re showing us what we don’t have.”

Below appear those six interlocking areas, with a note on their current realities and the opportunities to change them.

No Hunger

The reality: The U.S. society tolerates the fact that a significant amount of the population goes hungry. As Salvador pointed out to the EcoFarm audience, it’s not because of any lack of production.

The opportunity: To adopt a nationwide right to food. Salvador points out that this isn’t some sort of abstract hope, since it’s been proven to be affordable and effective in 1) places like Maine, which passed the nation’s first “Right to Food” Amendment; and 2) through COVID-induced support programs, which markedly reduced child hunger. “We know how to do this,” Salvador says. “We have done this.” He adds that progress can happen on a surprising turbo timeline: “Marriage equality, even four years before it became a law, was still something that seemed improbable or far off in the distance,” he says by way of comparison, “but once the tide turns, it turns quickly. Once the public gets behind this, it can become real faster than we think.”

Healthy Food

The reality: Research reveals the healthiest diets are mostly plant-based, heavy on grains, fruits, vegetables and nuts, with a limited amount of lean protein. But the food industry profits most mightily on processed foods, and its marketing reflects that.

The opportunity: Prevent advertising unhealthy foods in general and to minors in particular. “We need to treat ultra-processed food as the poison it is,” Salvador says. “It diminishes lifespan. We need to do with processed foods what we did with tobacco.”

Regional Food Webs

The reality: The U.S.’s food system is so dependent on long haul distribution that just three targeted strikes—to the port of Los Angeles, Highway 80 in the center of the country and the Mississippi River—would essentially paralyze the nation’s supply chain within days.

The opportunity: To support local and regional production that would not be vulnerable to long haul transport, which helps local businesses and creates local jobs. A compelling study of localizing a foodshed in Iowa reveals the shift is as attainable as it is desirable. “If we actually support local farmers and businesses to distribute food, it’s really good for our health, environment and local economy,” Salvador says. “It’s entirely viable, not a pipe dream.”

Agro-Ecological

The reality: The U.S. largely deploys a style of ag that depends on all kinds of inputs that farmers need to purchase, like machines, fertilizers and pesticides. That can outproduce sustainable operations in the short term, but those external inputs, symmetrically enough, externalize the real cost. “We pretend we’re running a factory that happens to be outdoors,” Salvador says.

The opportunity: Cultivate the insects, the fungi, the soil, the living plants themselves, holistically. “They have relationships with one another and they work together,” Salvador says. “If we allow them to work together they can capture carbon, produce healthier soils and do all sorts of things that reduce costs for things like fertilizers.” He adds that it’s about the whole agriculture community embracing that approach—not just the farmers like those attending EcoFarm—which makes it a matter of government policy. “We need to adopt a system that works with nature, not against it,” he says.

Socially and Racially Equitable

The reality: Land and wealth are locked up by those who received homesteads back in the 1800s. Additional land was taken from Native Americans a century plus before that. Ag land ownership is 97 percent white.

The opportunity: To redistribute ag land ownership fairly—without reappropriating it, as that would repeat the original sin. Salvador proposes that the government buy land from families whose next generation isn’t interested in farming and repatriate it to underrepresented groups, as part of another effort that seems far more unrealistic than it truly is. “We need to figure out how we get different people with different ideas and different objectives [onto farms],” Salvador says.

Climate Positive

The reality: Farms contribute to climate change. Ecological impacts of industrial ag include pollution from fertilizers and pesticides, greenhouse gas emissions, loss of biodiversity, soil degradation, erosion, pollinator harm and human health risks.

The opportunity: Farmland can help limit climate change rather than accelerate it. Sustainable practices are the key, as noted in the Agro-Ecological area. And it’s no mistake that, as agriculture becomes more focused on eliminating hunger, prioritizing healthy foods, regionalizing distribution, planning with agro-ecological wisdom and honoring social and racial equality, it also benefits the environment. “It’s a natural outcome,” Salvador says. “All these things work together. Stop supporting the industrial system any way you can.”

About the author

Mark C. Anderson, Edible Monterey Bay's managing editor, appears on "Friday Found Treasures" via KRML 94.7 every week, a little after 12pm noon. Reach him via mark@ediblemontereybay.com.

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/