November 19, 2021 – Welcome to Hollister, human population 38,687, unofficial livestock count closer to 200,000, where its greatest claim to fame is apricots, per Wikipedia.

There’s a compelling case to be made that it should be of greater renown.

Exhibit A: It is a world-class earthquake capital. (That seems a shaky claim, but check the frequency of tremors via Volcano Discovery.)

Exhibit B: The downtown district now hosts a burgeoning craft beer boom and is building out landmark new businesses in historic buildings.

Exhibit C: Its San Benito Wine Country is one of the best kept secrets in the world of wine. More about that in the upcoming Winter edition of Edible Monterey Bay.

And then there’s my favorite piece of evidence.

Call it Exhibit OMG: Hollister is home to the oldest sake brewery in the country and one of its largest makers, producing 1 million gallons a year.

Ozeki Sake was born way back in 1711 in the Hyogo prefecture of Japan.

There, in Nada-Gogō (which translates as “The Five Villages of Nada”), reside five clusters of sake breweries in the cities of Kobe and Nishinomiya—Ozeki’s home—making it the largest sake producing region in Japan.

The key to Nada-Gogō outpouring a quarter of Japan’s flagship adult beverage is the pure water that makes for great “rice wine.” (For those scoring at home, sake’s fermentation process makes it more of a rice beer than a rice wine, though it’s neither.)

A few years later—268 years to be precise—Ozeki reached new territory because it wanted North American audiences to have the freshest sake possible.

The two main reasons they chose Hollister as its U.S. HQ are the fundamentals of fantastic sake: great water and great rice.

The water here, according to Ozeki production manager Kenta Horie, enjoys mellow minerals—not too many, but with all the desirables a brewing specialist like him seeks—in a way that mimics the waters of Nada-Gogō.

Medium-grain rice they use is sourced north of Sacramento from multiple farms, that they review for quality with test brewing runs—and decline to disclose, for competitive reasons.

From that foundation, Ozeki launches a raft of different styles and flavors across sweet-to-dry and light-to-rich dimensions, bottled and draft, well upwards of 25 all told.

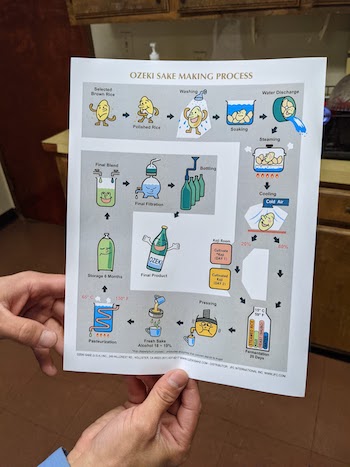

It invests in educating audiences on sake qualities, production process and pairings. Their brochure overflows with intel ranging from a cartoon-illustrated brewing flowchart to color-coded sake classifications.

A tidy glass case of small wooden figurines sits just inside Ozeki’s office doors. The understated but intricate scenes illustrate the time-worn process that creates their liquid.

Products, both large and small, are icons in the industry, like the 1.5-liter woven cask and the 180-milliliter One Cup Ozeki, which recently introduced a “One Love, One Cup” rainbow version.

The approachable vibe of their operation was on exuberant display at the most recent Hollister Wine & Beer Stroll. Ozeki reps poured their classic, full-bodied, dry-leaning Ozeki Junmai standard-bearer, and sweet strawberry and pineapple sakes too.

Yesterday I went by to check out the brewery, which is hidden right in plain sight on Hillcrest Road. One way to track it from further afield is the steam rising from its rice-preparation process.

Longtime Hollister resident and procurement assistant manager Seiichi Matsuda greeted me at the front of the office, and soon introduced me to Kenta, and the fascination at work began multiplying.

Kenta is the latest in a rotating cast of Japanese brewing specialists sent over from the mothership in Hyogo for U.S. stints that last as long as eight years.

He has trained in all elements of the artform, joining 10% of test takers in passing the sake expert assessor’s test, while earning the equivalent of a wine sommelier certification in the drink.

“They are very difficult challenges,” he says. “They test your [palate] and your knowledge. ‘Why is it smoky?,’ for example. I would have to understand and explain how the koji affected the flavor.”

It was after five years working at the home brewery that his higher ups honored his request to work in the U.S.

He’s now 11 months in, loving the mellow Hollister climate more than the humid extremes of his native land, as enthusiastic about evolving his English as he is about spotlighting what makes Ozeki unique.

He led a tour through the facility, which is closed to general traffic but open to private parties. (Meanwhile sake lovers and sake curious alike can purchase any Ozeki products at the office from 8am to 5pm weekdays.)

The sequence we traveled tracks the processing of the rice. First comes polishing, in tall columnar vats that funnel to connectors that fill bags for two weeks of demoisturizing.

The polish is dialed in by a specialized machine to remove about 70% of the outer layer of proteins, fats, iron and amino acids that could adversely affect flavor.

After the drying session, the rice gets an intense wash and steam at scale. When we stop by the massive conveyor belt along which the kernels are steamed, Kenta grabs a handful and starts smooshing it aggressively between two palms to evaluate it by feel.

“I make mochi with it,” he says. “Everyday I make mochi to make sure it is good.”

After it cures again it’s sent to a tumbler that, like much of the machinery on site, is imported from Japan, several decades into its service and purring with a similar sound the rice makes as it streams down various spouts.

“Very old, but very strong,” Kenta says.

From there, 20 percent of a rice batch routes to the koji room for exposure to enzymes that help convert starch to sugar. Then it’s added in with the rest of the rice, yeast and water in big fermentation tanks, where it bubbles for 20 days.

It’s that extra step of splitting and rejoining the base grain that differentiates sake from rice beer.

After up to 20 days of fermentation in soaring controlled-temperature tanks, the sake is ready for pressing, pasteurization, six months of aging, final blending, filtration and bottling.

Kenta tasted me through some of the different blends later.

Their solid standard bearer with the gold label and classic look is something that fans of the category know and enjoy. I like the dry version even more.

The daiginjo—made with a different 50-percent polish that expresses fruitier and alternative flavors—is an intriguing must-try. The cloudy nigoris also prove captivating and make my mouth water for sashimi to pair with it.

Flavored versions debuted in 2020 (strawberry) and this year (pineapple). They aren’t my jam, but are best sellers at local Japanese restaurants like Miyako in Hollister and Inaka in San Juan Bautista.

While onsite sales are going, online vending comes online early next year, with a tasting room to debut after that.

As we wrapped the tasting, Kenta asked if he could share something.

“I think good sake can make everybody feel good and have a good time with loved ones,” he said. “That’s why I want to make more good sake. I want everyone to know our company.”

It might seem strange to some that a sake powerhouse calls a cowtown home.

Not so for new EMB contributor Robert Eliason, who turned me onto Ozeki.

He acknowledges that it might appear out of place in a community that’s largely Latino and Western in its identity, but points out Japanese were among the original farmworkers in the areas, with baths and eateries that echoed their preferences. His guess is some sake brewers came with them.

“Japanese workers were the original work force for farms here,” he says. “It seems like it doesn’t belong, but culturally it does.”

Kenta seems to agree, at least on one level.

Back on his tour, he took a moment to direct me up a tall metal staircase to the eastern edge of a wide catwalk that opens up to the Diablo Range.

He described why, with a photo he took that morning, as the sun raised an eyebrow over the ridge.

“It’s my favorite place,” he said.

More at ozekisake.com. Ozeki can be found in many local restaurants, particularly Japanese-inspired outposts, and at its production facility at 249 Hillcrest Road, Hollister.

Send any feedback or tips to ediblefoundtreasure@gmail.com.

About the author

Mark C. Anderson, Edible Monterey Bay's managing editor, appears on "Friday Found Treasures" via KRML 94.7 every week, a little after 12pm noon. Reach him via mark@ediblemontereybay.com.

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/

- Mark C. Andersonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/markcanderson/