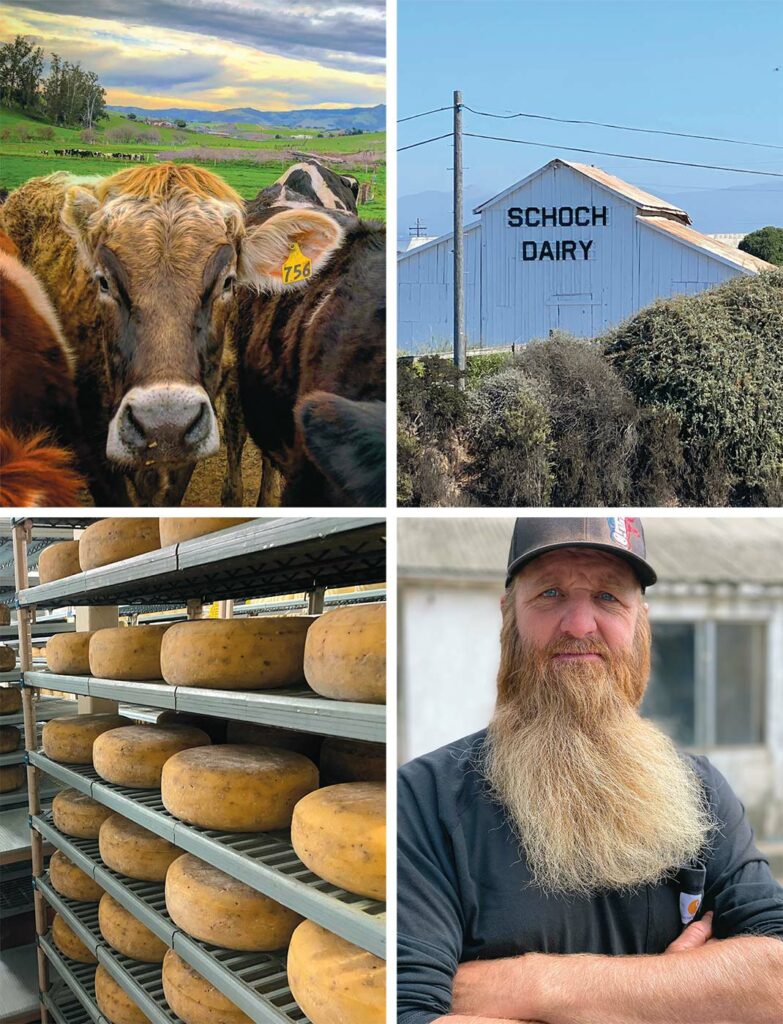

One of the Salinas Valley’s last remaining dairies faces the future

PHOTOGRAPHY BY MICHAEL KELLER

The Salinas Valley is often called the Salad Bowl of the World because the region produces an astounding 70% of the world’s lettuce as well as other vegetables. At the peak of summer production, more than 2,000 refrigerated trucks leave the area each day and deliver a staggering array of lettuces, cabbage, spinach, carrots, sugar beets and onions to the rest of the country. Given the economic and agricultural importance we see today, it might be surprising that the area was once home to a significant part of California’s dairy industry.

“There’s an old story I heard growing up that you could literally walk from Salinas to King City on the backs of dairy cows without touching the ground,” says Ty Schoch, whose family has operated Schoch Dairy here for nearly 80 years.

The Salinas Valley was home to 25,000 cows in the 1920s, according to farm bureau records. Spreckels, the low lying nextdoor neighbor to Salinas, grew sugar beets to make sugar. The tops of the beets were removed and used as cattle feed. By the end of World War II, new regulations on milk quality and increased competition for land from row crop farmers began to drive dairymen to the Central Valley. Cooperatives were forming in a sort of land rush, and overall herd sizes shrunk considerably.

At the northernmost point of the valley where farmland gives way to tree-covered hills is where Ernest Schoch and his brother Adolph purchased 100 acres in 1944. The site features the now iconic white barn emblazoned with the Schoch Dairy name. Many consider the barn to be the unofficial “Welcome to Salinas” sign.

SWISS DAIRYMEN

“My family came from Bauma, Switzerland, a mountain village about 30 miles east of Zurich. My great uncle Adolph and grandfather Ernest were dairymen,” says Ty Schoch. “The Spanish Flu of 1918 pretty much decimated the economy, killing many people and ruining any chance of profitably continuing the business. So they emigrated to the Salinas Valley in the 1920s.” Both men were in their 20s when they left Switzerland, a testament to their courage or a sign of the profound desperation they must have faced. Probably both.

Skilled dairymen were in demand so finding work was easy. Ty recalls some family stories. “My great uncle and grandfather would drive cows from Reliz Canyon, west of Greenfield, to Salinas. They got work at the Patrick Ranch in Chualar, at about the same time John Steinbeck wrote The Red Pony, which was on the nearby Gould Ranch in Salinas. The area was no doubt wild and full of migrants from the Dust Bowl—Okies, Swiss, Italians and Mexicans living in makeshift camps, competing for menial jobs, doing whatever they could. In the middle of all that, Mr. Steinbeck himself was writing about what he saw and turning it into some of America’s greatest works of literature, including The Grapes of Wrath.”

Ernest and Adolph both ended up working at what was then the largest dairy in the U.S. in Chualar, as herd manager and farm manager, respectively. The dairy milked 400 cows, all without automation, twice daily. The operational challenges the two men faced were massive. I would soon appreciate how impressive this skill was. Battle-hardened by the Chualar experience, Ernest and Adolph, now in their 40s, knew how to efficiently operate a dairy and partnered up to purchase the land and start Schoch Dairy.

The end of WWII marked the beginning of the Baby Boom, an era of boundless optimism, and with that came changes no one could have envisioned. Ernest and his bride Katherine started a family that included their son John, who grew up on the Schoch Dairy and lives there still. John married his high school sweetheart Mary and together they raised three sons who are guiding the dairy into its next phase: a creamery making cheese, yogurt and other milk-based products.

FROM MILK TO CHEESE

Since operating a small dairy didn’t make financial sense, the family needed to figure out other sources of income. “We needed to diversify, we all knew that,” says Ty. “Selling bottled milk directly to consumers was our first step. Then we moved into making farmstead cheeses.” The Schoch brothers purchased raw milk from their father and began selling it at farmers markets under the name Schoch Family Farmstead.

Ty’s brothers, Seth and Beau, enrolled in a cheesemaking course at Cal Poly, and Beau began making cheese in his home kitchen. “Early efforts were not very good,” Beau recalls with a laugh. “At first I was making it in a 1-gallon pot and then in a 2-gallon pot, and soon outgrew my kitchen. I was always cleaning up.”

The Schoch brothers knew they were on to a good thing, making a true farmstead cheese with milk from their own cows. “We are able to pump warm milk directly from the milk barn to the cheese or yogurt vat,” says Ty. “This milk has not been stored, hauled, cooled, heated or overly pumped and agitated. The fats in milk are fairly fragile and degrade with time and easily damaged by drastic changes in temperature, jostling and pumping.”

“Unlike commercially produced cheese, our milk does not experience these stresses, and that results in a more flavorful, pristine cheese,” he adds. Raw cheeses are also easier to digest for some people because certain enzymes, such as lactase, have not been denatured by pasteurization.

FAMILY BUSINESS

At Schoch Dairy, Seth manages the herd, John does the milking, Beau and Ty do the bottling, and then make and package the cheese. Mary handles the bookkeeping and administrative chores of the business. There are two part-time employees, but the family does everything else.

Mary Schoch is a soft-spoken lady with eyes that match her gentle voice. She supports her husband and “the boys” in many ways, preparing meals and managing the dairy’s back office. The lone woman in the family, Mary is strong, but a lady in every way. This is how she describes her husband’s work ethic: “He gets up at five o’clock every morning and comes back to the house for lunch and a nap around noon. Then he’s back out working until early evening, seven days a week. The cows don’t care if it’s Christmas Day or Tuesday. The cows require milking twice a day, no matter what.”

As impressive as that sounds, it really hits home when I join John in the milking parlor to watch him work. “We milk 110 cows twice a day. They all seem to line up the same way; it’s kinda funny how they do it,” he says.

John stands in a walled 10- by 5-foot concrete pit so that the cows’ udders are about at waist level. He deftly wipes the udders with a disinfectant before attaching the mechanical milking devices to them. A switch is thrown and the milking commences. The cows appear to enjoy it. They feed while they’re being milked and are sometimes reluctant to stop after the milking attachments are removed.

Each cow is numbered. “This one, number 51, will only come into this one stall to be milked,” says John with a laugh. “This other one, 139, won’t leave until you pet her on the head.” Sure enough, number 139 stops in front of the pit and just stands there. I’m ready to leave and 139 just won’t move. Finally she turns and looks at me. I put my city-slicker hand on her head between her eyes and rub it up and down. It feels hard and bony but with a coat that’s different than any other animal I’ve ever felt. A few seconds later 139 is apparently satisfied with my petting and walks on to rejoin the other girls outside.

I ask John how long it takes to milk 110 cows. He answers without any hesitation.

“Three hours and 40 minutes.” Twice a day? “Yep.”

Out at the cheese making facility, I put on a hairnet and oversized rubber Birkenstock-like coverings for my shoes. The large slip-ons feel strange, like I’m going to walk out of them with each step, so I shuffle like I’m cross-country skiing across the wet concrete floors. It’s chilly but not cold. Ty and Beau take turns explaining the process for making cheese and yogurt. Both men know their stuff and explain it clearly without hesitation.

I’ve been an enthusiastic buyer of their Swiss-style yogurt for many years, a pourable product that comes in a glass bottle with an illustration of the barn on the front. Their newest variety is a firmer product similar to Greek-style yogurt, which has the same ingredients but without the whey. To make it, Beau fills cheesecloth bags with yogurt and lets the whey drain out. Taste comparisons have me leaning towards the thicker yogurt, but frankly I don’t care. They’re both excellent.

Racks of aging wheels of cheese fill the refrigerated room and are turned over daily. The room itself is heavily insulated. A sensor detects when the outside air is cooler than the air inside and it pumps the cool foggy night air in, reducing cooling costs. A pool of brine stands at one end of the room. Freshly formed wheels are given a bath in the salty amber liquid.

“How do you get them out?” I ask innocently. In my mind they’re sticking both arms in the brine up to the shoulder and making a mess of their shirts, the floor, everything. “They float,” says Beau politely.

He quickly pivots to the room next door, a new cheese “cave” that is nearly ready for their planned soft cheeses, as well as harder cheeses for grating, similar to Parmesan. It’s cooler and has higher humidity with stainless steel walls and wooden racks ready to store the new products.

The tour is nearly complete. I am relieved to ditch the rubber Birkies and fashionable hair net before Beau takes me into what will eventually become the new retail store. A single hand-washing sink is all that’s in the room so far. The floor is stamped concrete, the walls are wooden panels taken from the original family cabin. There’s a walkup counter for shoppers and an area that will eventually become outdoor seating for enjoying cheese, and other food items.

“We’re right off the 101,” says Beau, outlining their vision for the new shop. Signage, customer parking and picnic tables under a network of stringed lights are still in the planning phase. An enthusiastic invitation to return to see the new addition to the dairy is extended.

With my arms full of artisan cheese and containers of yogurt, the family gathers around me to say goodbye. I see John in a new light now, Mary too. This is a working dairy that’s their world, one not shown to many outsiders. It’s obvious the family’s workday has been interrupted to accommodate me, and I suddenly feel humbled and honored by their gracious hospitality.

The Schoch family is quietly proud of their heritage and rightfully so. They gathered for a family photo, and if thought balloons were visible I’m certain all five of them would be thinking of what they had to do next, and just how long this way of life would last.

Salinas and urban growth are getting closer by the day. The low roar of Highway 101 can be heard in the distance, drowning out the moos of cows and the sound of refrigerator compressors. John and Mary have worked hard for many years, but give no hint of retirement or even slowing down. For them it must be something to be able to look at your life’s work at every turn. Now they’re handing the baton to their three sons.

I’ve met and dealt with dozens of farmers in my life and they all seem to wear their hard work like a badge of honor. Dairymen are the toughest because they never get a break. The harvest never pauses for them and they persist without complaint. They have milk in their blood.

SCHOCH FARMSTEAD CHEESE

The Schoch family crafts semi-hard aged cheeses with natural rinds, which are available in full wheels or partial wheels by special order, or in individually wrapped wedges at farmers markets and select stores.

Schoch Monterey Jack is the only Monterey Jack cheese still made in Monterey County. The lineup includes:

East of Edam is a play on Steinbeck’s novel, East of Eden, written about the Salinas Valley. “This is a Dutch-style mild cheese aged four to six months with a subtle nutty, but complex taste,” says Ty.

Gabilan is an Alpine-style cheese, reminiscent of Gruyère. It’s firm with a nutty flavor and aged 4 to 6 months.

Junipero is a smooth textured Swissstyle cheese, sweet and nutty, aged 3 to 6 months.

Monterey Jack has a buttery, robust flavor and is aged 2 to 4 months. Mt. Toro Tomme is aged for 2 to 4 months, and is buttery with a tangy, lactic finish.

Santa Rita is what Beau describes as a Belgian Trappist-style cheese. The rind is washed with beer until it’s covered in mold. Over the next 2 to 4 months, it evolves into an orange colored rind with a pungent aroma but creamy texture. “The Trappist monks brewed their own beer,” he explains. “This style of cheese was very hearty, and they discovered that it served as a kind of replacement for meat on Fridays, when they were not permitted to eat meat.”

About the author

Michael Keller has an insatiable appetite for food, and not just eating it. He has worked in commercial agriculture for three decades, and spent more than 20 years as a vendor at the weekend Monterey Bay Certified Farmers Markets selling chai, looseleaf tea and his pastry chef wife’s popular scones and preserves.

- This author does not have any more posts.