Traversing the lands, characters and foods that fed John Steinbeck’s soul

LEAD PHOTO BY KODIAK GREENWOOD • ADDITIONAL PHOTOS BY MARK C. ANDERSON

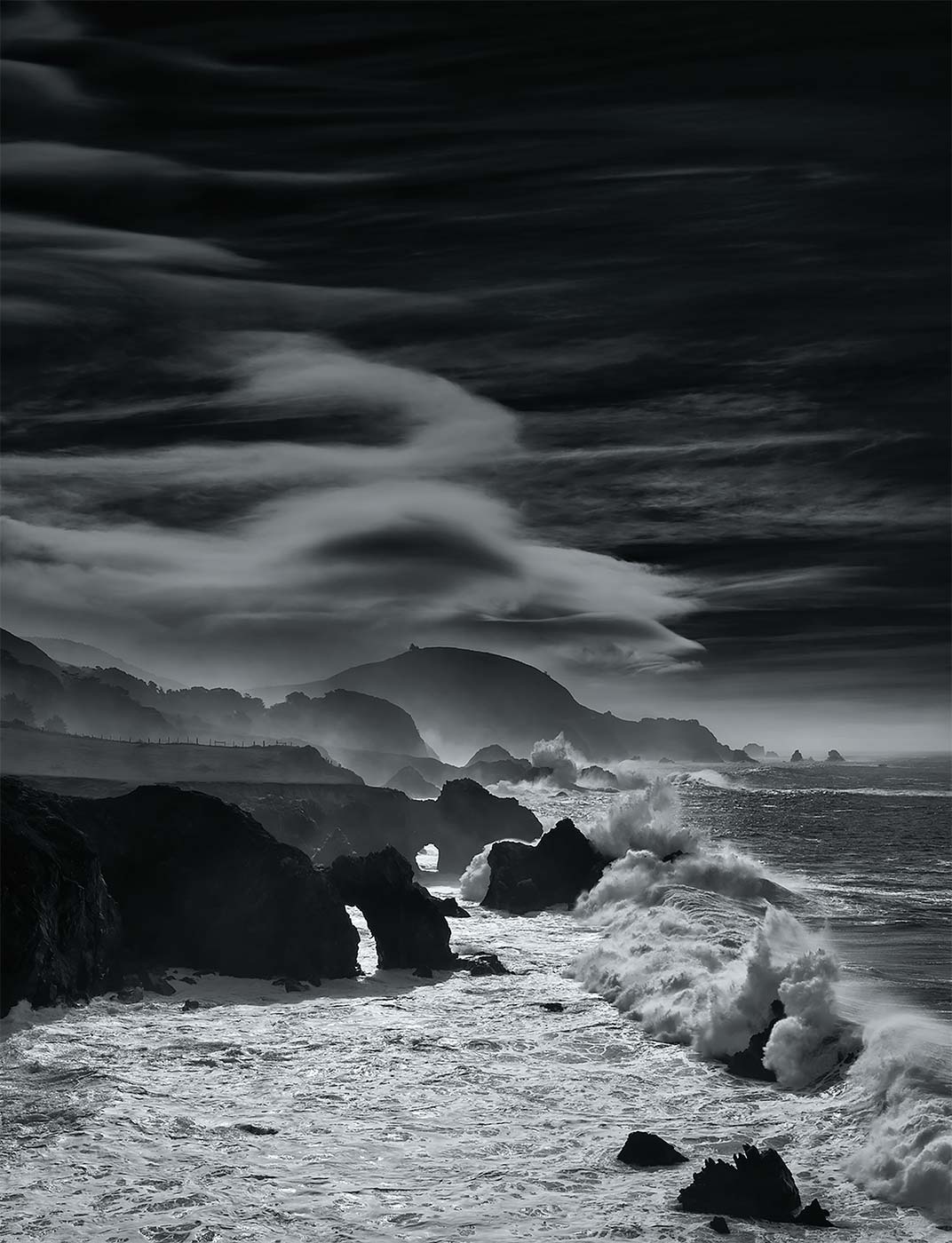

About fifteen miles below Monterey, on the wild coast, the Torres family had their farm, a few sloping acres above a cliff that dropped to the brown reefs and to the hissing white waters of the ocean. It was a foggy Friday in June and my friend Marlene was reading aloud the opening paragraph of “Flight,” John Steinbeck’s 1938 short story about a boy named Pepé Torres who was forced to flee his family’s farm after killing a man.

I had read the story in high school and was captivated by the coming-of-age parable and a boyhood doomed. So Marlene and I drove down Highway 1 toward Big Sur to see if we could find the plot of land where the fictional Torres family might have lived. I mapped out our route on GPS, but about five miles into our trek, we lost cell service and found ourselves, like Pepé, guided only by the outline of the coast.

On our left were granite mountains towering over grassy fields thick with thistles and tufts of white yarrow. We drove past Carmel Highlands and crossed the Garrapata Creek Bridge, which was built in 1931 at about the same time Steinbeck wrote Tortilla Flat, a novel about men on the fringe of society in post- World War I Monterey.

As we inched our way south, I had to wonder: Did Steinbeck’s wild coast still exist? Would the sloping acres and ancient redwoods he so vividly described in “Flight” reveal themselves? Or was Steinbeck’s imaginative telling all that survived?

“The real feeling of Steinbeck’s work is inland, among the ranches and farms of the Salinas Valley.”

We approached Notleys Landing, a spit of land at the mouth of the Palo Colorado Canyon. And there, a grassy bluff appeared that rolled down to the sea before dropping sharply and slipping into a cove of frothy waves.

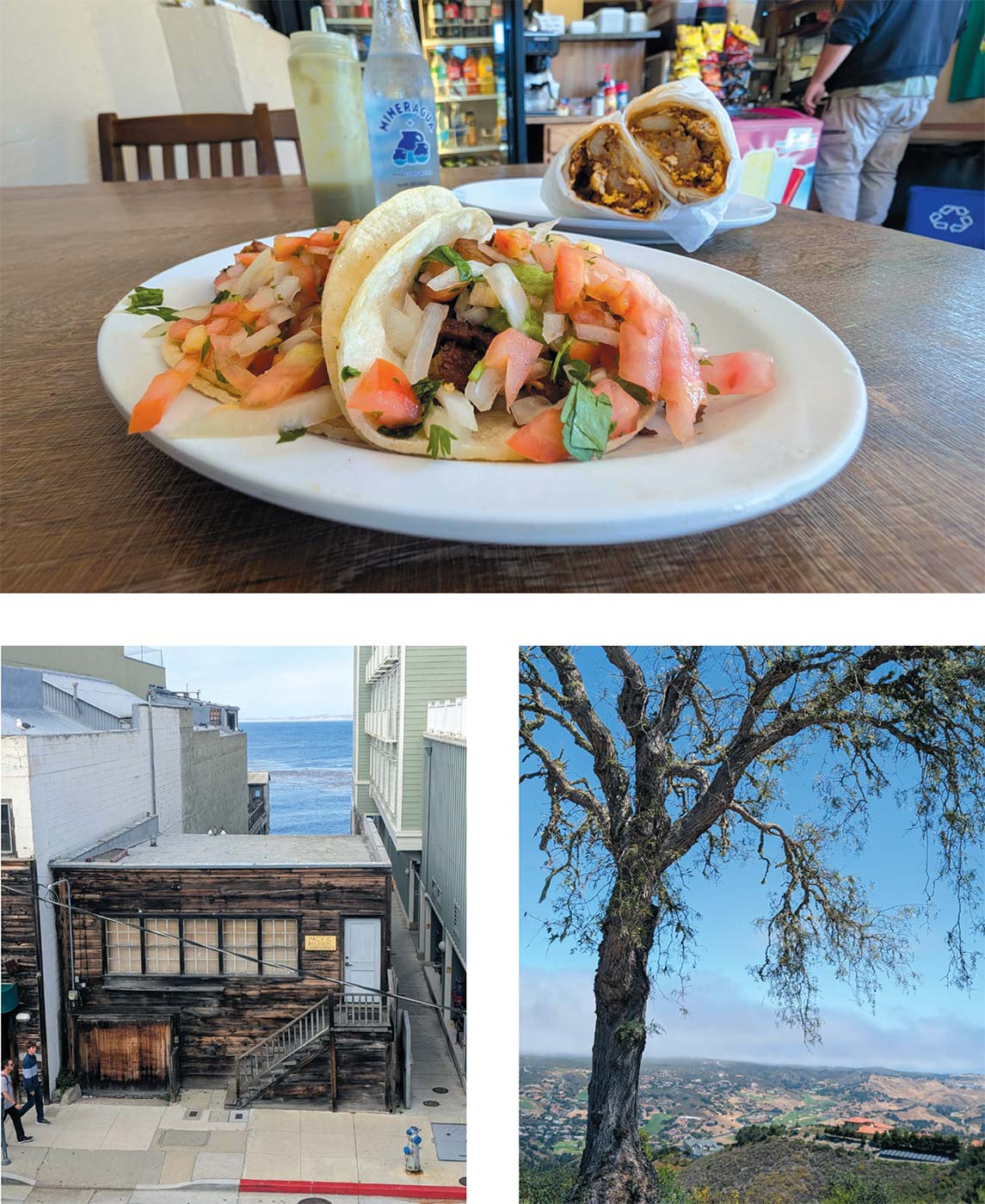

I turned to Marlene with delight and said, “I think we found it.” After our visit to Big Sur, Marlene and I decided to make our way to Kathy’s Little Kitchen in Carmel Valley, a one-room storefront that serves up plates of carne asada, chile rellenos and the occasional menudo.

It is the kind of unfussy kitchen that would have thrived 100 years ago and that Steinbeck or his characters might have frequented. Patrons order at the register from a board above the kitchen. When we were there, a line of locals snaked out the door—a painter, a couple of tree trimmers and a man in a cowboy hat and dirt-caked boots. I ordered two carnitas tacos. The meat was crisp and fragrant, and wrapped in a pillowy tortilla. It was inexpensive and fast, perfect for journeymen on the go.

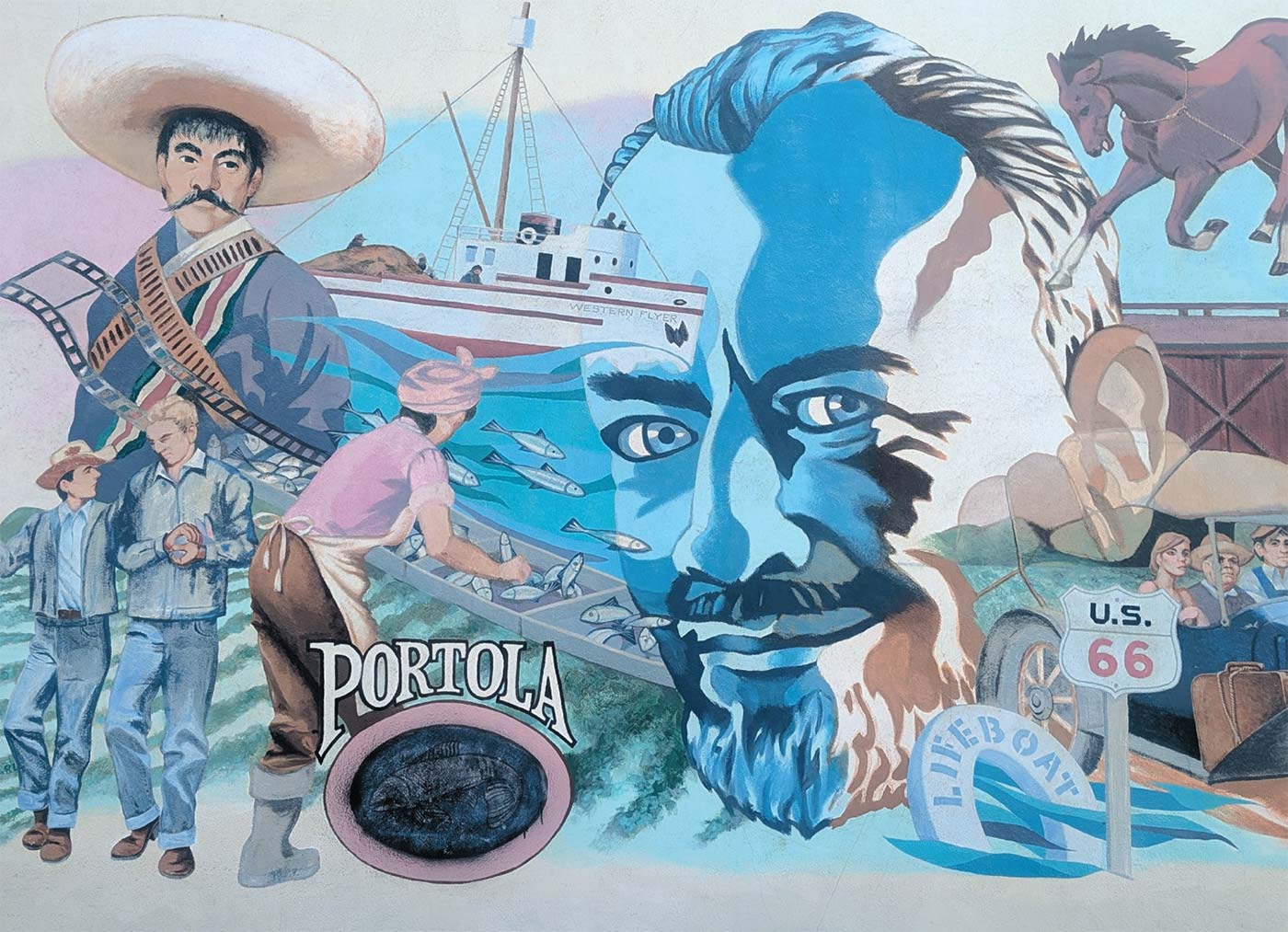

Few authors have captured the struggles of California’s working class as well as Steinbeck. But as much as Steinbeck found meaning in the lives of lonely drifters and immigrants, he did so, too, in the land. As much as anything, Steinbeck wrote about places that continue to make up so much of the agricultural community of the Salinas Valley.

From the fields along Highway 68— where migrant laborers crouch over rows of lettuce—to the docks along Monterey, his imagery transcends the descriptions of the food people ate, illustrating their domestic life, camaraderie, emotional hunger and social status.

The Pacific Biological Laboratories building at 800 Cannery Row served as the workshop of marine biologist Ed Ricketts, who inspired the character Doc in Cannery Row. Today it remains perhaps the most famous Steinbeck landmark and hosts limited tours.

But there are less renowned—and more accessible—places to encounter reminders of his presence.

At Trotter Galleries on Forest Avenue, across from Pacific Grove’s City Hall, there is currently a collection of photographs, magazine clippings and other items that celebrate Steinbeck’s life and work.

A black Royal portable typewriter said to have belonged to the author is prominently displayed. There, too, is an original door from his cottage, the paint faded and chipped, and a small felt-covered writing desk. Glass cases are filled with notes written by Steinbeck and his third wife, Elaine, who played a significant role in protecting his legacy.

There is a stretch of rolling hills and farmland on Highway 68 between Monterey and Salinas that reflects some of Steinbeck’s most celebrated works.

“The coastline is gorgeous,” says Peter Van Coutren, the archivist at the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University. “But the real feeling of Steinbeck’s work is inland, among the ranches and farms of the Salinas Valley.”

In The Pastures of Heaven, a collection of interwoven stories set in a rural valley, a rancher threw a barbecue for 50 guests who dined on grilled steaks and chicken served with strong beer.

Clearly, this rancher had money. Other Pastures of Heaven characters did not. Two penniless sisters sold homemade tortillas and enchiladas in their home after their father died. But their endeavor ended in heartache. The duo earned little money, and turned to prostitution.

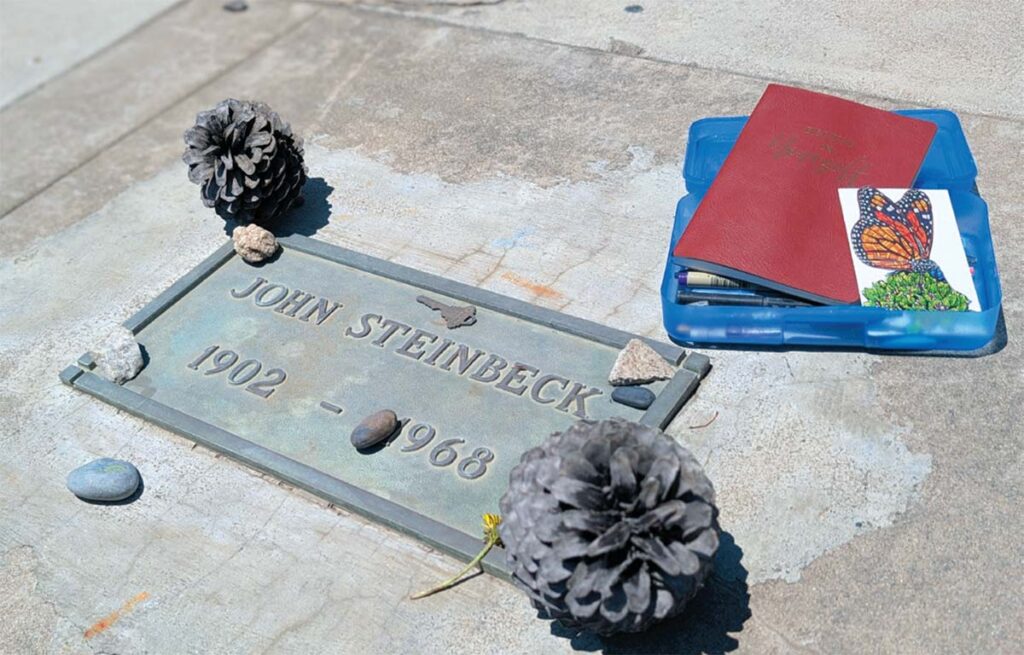

At his humble Salinas grave, Steinbeck pilgrims leave stones, cards, coins, keys and bundled notes that often quote his words, including, “All plans, safeguards, policing, and coercion are fruitless.”

The Toro Place Cafe along Highway 68 reminded me of a place Steinbeck might have written about. It was crowded with pickup trucks when Marlene and I drove by on our way to Salinas.

The restaurant opens at 6:30am, in time for the early morning farm crews looking for hearty breakfasts of eggs, biscuits and mugs of black coffee. By early afternoon the farmers are mostly gone and replaced with commuters and tourists who stop for lunch.

Workers still pick crops and load boxes onto trucks in the fields nearby. Steinbeck explored corporate greed and exploitation of migrant workers in much of his writing about the Salinas Valley. But the wail of motorcycles from the Laguna Seca Raceway nearby echoes among the hills, a reminder of the area’s expansion.

Pastures of Heaven was published in 1932, its setting modeled after the Corral de Tierra Valley. We climbed the Laureles Grade towards Carmel Valley to get a better view of the area and saw knots of oak trees punctuated by golden fields and housing subdivisions that multiplied over the years as more people moved there.

Corral de Tierra sits at the foot of Castle Rock, a sandstone cliff that figures prominently in Pastures of Heaven and where Steinbeck played as a child.

To be sure, the area is developed with a golf course and more. But some parts still retain old California charm.

Wild turkeys nestle under oak trees thick with moss. One house is tucked behind an eight-foot-high cactus fence. Others have sturdy walls and colorful tiles that evoke old haciendas.

Any study of Steinbeck, who received the Nobel Prize in literature in 1962, should include a stop in Salinas.

Much has changed since Steinbeck lived there. The former Sang’s Cafe, where Steinbeck dined regularly, is now La Gran Diabla, a technicolor cantina named after a she-devil. The National Steinbeck Center was built on Main Street, a few blocks from his childhood house (see sidebar, p. 56). It is an educational trove. A large map at the Steinbeck Center highlights the Oldtown Salinas area that Steinbeck wrote about in East of Eden. On display is the camper he drove around the country with his dog, Charley.

Steinbeck is buried in Salinas, not Sag Harbor, New York, an artist community on Long Island where he mostly lived until his death in 1968.

Garden of Memories Memorial Park is located on a noisy stretch of Abbott Street crowded with welding equipment stores, fast-food chains and industrial machine shops. A hand-painted arrow directs visitors to a scrubby patch of grass near a family plot. There, an unadorned marker bears Steinbeck’s name.

Admirers arrange stones, coins and plastic pens on the marker in memory of the author. It is a humble grave—fitting, I imagine, for a man who spent much of his career writing about the working class.

I believe he wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.

THE STEINY DIET

Humble eat-and-drink destinations to channel Monterey Bay’s bard of the blue collar.

On Feb. 27, 2025, on what would’ve been John Steinbeck’s 123rd birthday, the C Restaurant next to Doc Ricketts’ Pacifi c Biological Laboratories on Cannery Row staged a “Steinbeck Dinner.”

The author would’ve likely smiled at Exec Chef Matt Bolton’s menu of abalone, Salinas Valley greens, steak and potatoes (albeit fancied up), and Pastry Chef Michelle Lee’s “beer milkshake” with chocolate-Guinness ice cream, all dishes that drew literal inspiration from his books. The $140 tag, not so much.

Here appear places much more his price point, across Steinbeck Country, listed south to north.

BIG SUR TAPHOUSE

The only real locals spot on the South Coast earns that loyalty from the everyman with bargain-grade daily specials, a strong craft beer lineup and dog-friendliness (I see you, travelin’ Charley), plus the connected deli-bodega’s hefty sandwiches, burritos and other essentials.

Noon–9pm daily (deli 7am–8pm)

47520 Highway 1, Big Sur

bigsurtaphouse.com

PEARL HOUR

When a woman sitting at the long antique bar got up to use the restroom, her companion volunteered some information to Pearl Hour owner/ operator Katie Blandin (see sidebar, p. 59). “She’s Steinbeck’s granddaughter,” Blandin remembers the man saying, “but she doesn’t want to make a big deal about it.” Then he added: “I think he would really approve of this place.”

6pm–close Wednesday–Monday (closed Tuesday)

214 Lighthouse Ave., Monterey

pearlhour.com

PHIL’S SNACK SHACK & DELI

At the aff ordable little brother to Phil’s Fish Market & Eatery, the industrious clientele, the burly burgers, the spot-on “shack” name, the basic picnic benches perched by Elkhorn Slough… all speak Steinbeck’s language. On top of that: 1) The best-selling calamari sandwich comes on sourdough; 2) The Western Flyer boat Steinbeck took to Baja California with Doc Ricketts—now retrofi tted for modern science and education expeditions like its fi rst such trip this summer— often docks at nearby Moss Landing Harbor; and 3) Sourdough stars as a staple for their Baja mission, as Steinbeck observes in The Log from the Sea of Cortez, writing, “Our sourdough bread came out surprisingly well…”

7am–3pm weekdays, 7am–2pm Saturday, closed Sunday

7912 Moss Landing Road, Moss Landing

philsfishmarket.com/snack-shack

THE STEINBECK HOUSE

It’s not surprising that the famous author ate here—his childhood home, where he was also born. More surprising: How much hustle and heart the home’s volunteers put into seasonal lunches serving items like walnut “meat” loaf, tri-tip with chili beans and “Steinbeck brownie pies.” “It’s all about people getting to know more about the history of the house,” says Kathy Culper, the nonprofi t SH’s president, “and the beauty of the produce that comes out of our valley that we showcase.” The latest edition of the Steinbeck House Cookbook debuts in the downstairs Best Cellar Gift Shop this December, with new Blue Zones–certified recipes.

11:30am–2pm Tuesday–Saturday (gift shop until 3pm)

132 Central Ave., Salinas

steinbeckhouse.com

COWBOY CORNER CAFE

Steinbeck and his sister Esther were close (he’d frequently write from the road, and visit Esther’s house in Watsonville whenever he could) and remain so (they’re buried next to each other in Salinas). So a kindred spot in her Pajaro Valley farming community merits mention here. Particularly an old-school, from-scratch and breakfast-lunch classic like the Cowboy Corner Cafe, run by Juan Diaz, who rose from dishwasher to owner, after coming to California— East of Eden style—looking for a better life.

946 Main St., Watsonville

cowboycornercafe.com

About the author

Laura M. Holson is an award-winning feature writer who worked for The New York Times for more than two decades and founded The Box Sessions, a creativity company. She has traveled extensively within Italy, including Sicily where she visited the villages where her grandparents were born.

- Laura M. Holsonhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/lauramholson/