PHOTOGRAPHY BY DORIANA HAMMOND / WEST CLIFF CREATIVE

Meet the farmer behind the happiest pasture-raised chickens around

Demand for Fogline Farm chicken is brisk. Fogline’s Cornish Cross broilers, a breed developed for perfect fit in a standard oven, can be found on menus of fine dining establishments from San Francisco to Big Sur, and they’re popular with shoppers at seven Central Coast farmers’ markets. Restaurant chefs and home cooks alike can taste the idyllic upbringing of Fogline’s flocks, raised at the edge of the Pacific Ocean on a ranch near Año Nuevo State Park.

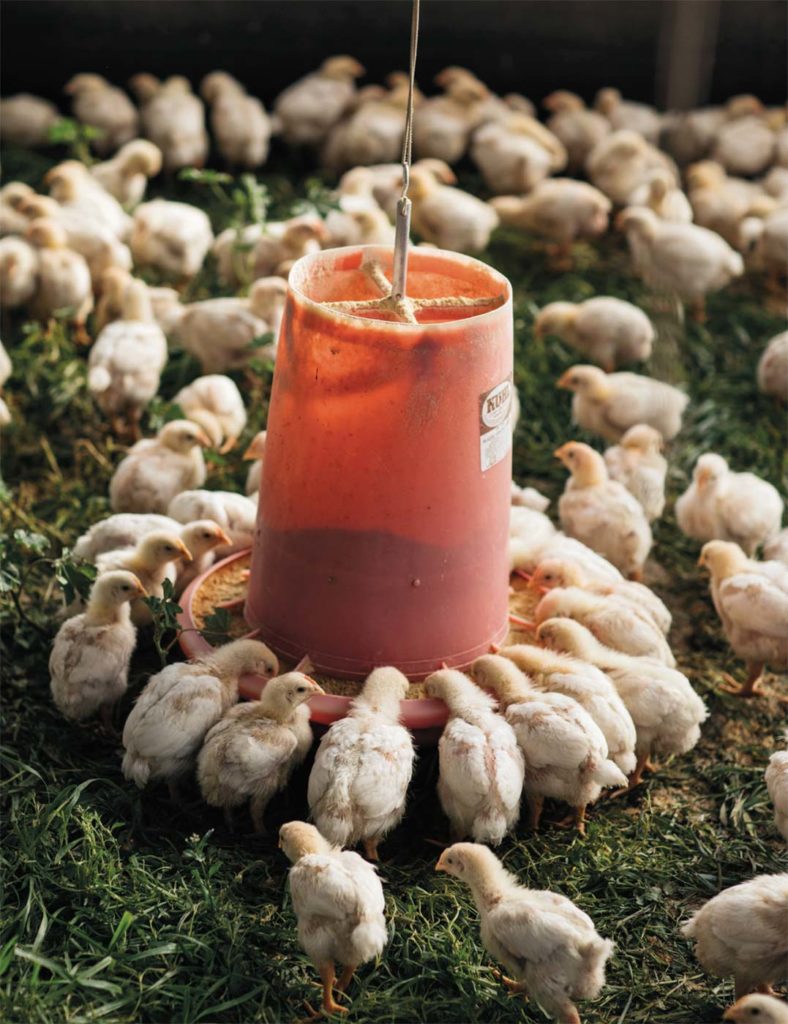

The chilly morning I visited, sparrows twittered in the clutches of a spindly apple tree in front of a row of dark green shipping containers that are used as brooders. Inside one of the repurposed containers, hundreds of week-old chicks huddled around poultry feeders, warmed by overhead gas heaters and a cozy layer of peat moss underfoot. Beyond the brooders, an emerald sea of tangled pastures extends out to the horizon, eventually meeting sand dunes that undulate to the Pacific.

Fogline Farm was started in 2009 by a trio of graduates from the Center for Agroecology at UC Santa Cruz and is named for the place it began in the Soquel hills. Today, the operation is led exclusively by Caleb Barron and is staffed by five full- and 10 part-time crew members, who tend the flocks, butcher and pack meat, organize the warehouse and travel to weekly farmers’ markets from Oakland to Monterey. On a calm day, Barron can hear elephant seals while working at his open-air picnic table desk. He is chicken guardian in chief; president of operations and brood manager charged with feeding, observing and caring for his flock at every stage of their sixweek life cycle.

With a sturdy build and broad smile, he wears a trucker’s hat, flannel shirt and a five o’clock shadow. His light Minnesotan accent emanates the kind of warmth and fortitude necessary to survive a Midwestern winter. Fond of jam bands, free of pretension, Barron isn’t the sort of guy you’d imagine obsessively checking his phone and pacing when he’s away from the farm, but that’s how he describes his dedication.

His affinity for working in the sunshine with hands in the dirt developed at an early age. Barron recounts being raised by “suburban hippies” in Minneapolis where he “grew up outside in the garden or in the backpack,” absorbing a back-to-the-land ethos from his parents.

Now 41, Barron is father to a toddler, husband to a local elementary school teacher and more than a decade younger than the average U.S. poultry farmer. He is a self-proclaimed “liberal arts kid” with a background in geology and a palpable yet pragmatic passion for healing our broken relationship with the earth through holistic livestock management.

Barron’s journey to farmerhood was shaped by two facets of the concept of sustainability: self-reliance and soil conservation. As a high school senior, the chance discovery of an article torn from Outside magazine led him to defer college and head to Denali National Park in Alaska. There, he made a perilous pilgrimage to Fairbanks Bus 142, in which storied adventurer Chris McCandless of the film Into the Wild left his diaries and ultimately his body in 1992. “We had to cross a river where somebody had died earlier that year,” Barron recalls. “It was a journey.” While in Alaska, Barron pored over memoirs of survivalists whose wilderness rites of passage had taken them to remote reaches of the continent to explore the lost art of self-sustenance.

After finishing a bachelor’s degree in geology at the University of Puget Sound, he was eventually drawn to the farm apprentice program at UC Santa Cruz. He credits the poetry of Gary Snyder with nudging him “back to the land” and toward the California Coastline. Reflecting on his apprenticeship, he readily admits that he “didn’t really care about the nitrogen cycle,” but he loved “the community and just being outside and working with my hands.” A second apprenticeship with animals at scenic Pie Ranch, just a quick jaunt up the road from Fogline’s current location, sold Barron on livestock management.

For the first three years of Fogline, the three founding friends could not pay themselves. Then their land lease expired and the property sold to a new owner. Partners Johnny Wilson (“the veggie guy”) and Jeffrey Caspary (“the fruit guy”) left to pursue other opportunities, Fogline abandoned row crops and Barron relocated the operation from Soquel to a property near Wilder Ranch, and then to Año Nuevo.

He credits the poetry of Gary Snyder with nudging him “back to the land” and toward the California Coastline.

In the present location, pastured chickens work in rotation with cattle from TomKat Ranch to gradually restore depleted, compacted soils that once supported a pesticide and fertilizer-laden commercial flower operation. Fogline currently operates under a precarious one-year lease. “I’m taking a huge risk in being here,” Barron says, adding that he is also unable to raise pigs, as he once did, due to terms of the lease. “Nobody wants pigs on their land.” But he is quick to point out that despite the challenges, he has the most beautiful commute in the world. The natural tranquility of Fogline’s North Coast surroundings impose an artificial ease on the epic hustle that defines a modern, earth-centric poultry operation.

At the onset of the pandemic, Barron assumed his business would have to shut down. Instead, direct-to-consumer sales boomed, spurring the creation of an online store. As restaurants shuttered their doors, demand from consumers, buyer’s clubs and grocery delivery services such as Locale and EatLocal.Farm swelled.

He is keenly aware of the high price his customers pay for Fogline’s chickens and cautious about passing along the rising costs of his operation to consumers. “Feed prices have skyrocketed during the pandemic, especially organic,” he says, standing at the mouth of a mobile chicken house attached to a tractor. In addition to maintaining exceptionally clean and comfortable accommodations for the farm’s infant broods, elder poults (a mere four weeks old) are released into king-sized, airy, hoop houses on skids. Protected from predators, they hunt and peck before being scooted along to a fresh patch of weeds and insects. The mats of organic manure they leave behind are later broken up and pressed into the soil by four-legged grazers. Barron manages every sale and nearly every meal and movement of his animals, 52 weeks a year.

When asked about the move towards plant-based diets as a way to reduce one’s carbon footprint, Barron replies that he “firmly believes that animal agriculture is a necessary part of healing and maintaining land.” His beliefs are supported by recent research quantifying the high carbon sequestration capacity of multi-species pasture rotation systems like Fogline’s. Due to these positive findings, combined with the bad press on carbon emissions from the livestock industry, the meat market is now awash in meaningless labels, such as pastured, natural, climate friendly and thoughtfully raised. (See story on labeling)

He distances himself from hollow monikers not backed by thirdparty certification, even the term regenerative, which he sees as a mere marketing ploy in many cases. How can consumers avoid these red herrings when shopping for truly sustainable protein that has enjoyed a good life in the sunshine while giving back to the land on which it grazed? In Barron’s words: “It sounds stupid, but know your farmer.”

Avgolemono Soup

Courtesy Emily Beggs, owner of Kin & Kitchen

This lemony Greek variant of a classic comfort dish (chicken soup) incorporates both Fogline’s chicken and eggs—raised at the farm by Antonio Reyes.

About the author

Emily Beggs is founder and lead chef of Kin & Kitchen, which specializes in ecologically-minded private chef services for clients throughout California. She has a background in the anthropology of food and nutrition, and the menus she develops meld wellness-promoting ancestral recipes with local ingredients to create intimate and nourishing feasts.

- Emily Beggshttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/emilybeggs/

- Emily Beggshttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/emilybeggs/

- Emily Beggshttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/emilybeggs/

- Emily Beggshttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/emilybeggs/