Identity and complexity resonate in a glorious chilled soup

PHOTOGRAPHY BY PATRICK TREGENZA

Gazpacho is all about the tomatoes, and their ability to channel sunshine and a summer breeze in one juicy bite. Well, not entirely.

It’s also about the discovery of a dish you suddenly can’t get enough of. It’s about tasting several vegetables in balanced unison. It’s about identity, making the best of what the land near you yields, and exploration.

It’s about history, memory and context.

And—nostalgia aside—cooking gazpacho is about finding connectionas where they didn’t seem to exist. Gazpacho as a concept is certainly ancient. When the Spanish peninsula was a Roman province, gazpacho’s ancestor salmorium—garlic pounded into a paste with bread, vinegar and oil—nourished field workers.

By the 16th century, tomatoes sailed from the New World and sunny southern Spain’s warm weather allowed them to flourish. Combined with the centuries-old salmorium, the result was gazpacho Andaluz, the widely known and beloved cold summer soup, distinguished by its smooth texture and refreshing taste.

There are multiple regional interpretations, forming a whole gastronomic gazpacho map. You can tell a lot by which type of gazpacho someone likes, or which their grandma made.

Salmorejo, also from Andalusia, provides a heartier version, with grated or roughly chopped ingredients, garnished with hard boiled egg and serrano ham. From neighboring Extremadura, “campero” or “extremeño” gazpacho omits tomatoes.

Ajo blanco is the primeval recipe present in regions with strong Arab influences—not one for mild flavor fans, thanks to layers of garlic, almonds, vinegar and olive oil— with floating green grapes serving as the obligatory garnish. Without the grapes it works as a light mayonnaise, perfect for lobster and shrimp or with a collection of fresh herbs. And the garlic intensity can be tamed by blanching in water before blending.

A close relative from Málaga, gazpachuelo, has the same base, warmed up as a brothy background for seafood and potatoes with the addition of egg yolks. A more distant cousin from central Spain, gazpacho Manchego, feels like the complete opposite, a game stew topped by old bread.

Some recipes for gazpacho Andaluz start by mentioning you absolutely must grow your own tomatoes.

Yes, that might sound extreme, but people are really serious about their gazpacho. (And less strict versions ask that you let your farmers market haul sit gently in the windowsill where it gets morning sunlight.)

QUOTE Yes, that might sound extreme, but people are serious about their gazpacho.

Either way, you certainly need to have sweet, juicy, aromatic, summer-ripe tomatoes as the base.

Cucumbers are also crucial, as are garlic and bell peppers, red or green, depending on preference. Bread, although not essential, provides a binding, uniform, almost creamy consistency. This is not the moment to use crusty sourdough as it might show up as dark speckles in the result.

Sherry vinegar and the best olive oil you can get your hands on are also critical. Seasoning is normally only salt, although some souls from Sevilla swear by a pinch of cumin.

Occasionally recipes suggest roughly chopping the ingredients and allowing them to marinate with salt. It doesn’t make a significant difference. The step that really matters is to blend it for longer than you would consider normal, and then strain it, turning it into a velvety delight.

Refrigerating gazpacho before serving, meanwhile, is non-negotiable. You can even throw ice cubes in the blender to make sure nothing heats up.

Serve in bowls or glasses—though there is always the option of drinking gazpacho straight from the pitcher while at the refrigerator door.

That’s what the protagonists did in Pedro Almodóvar’s Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown. Sharing it symbolized a connection of identity, allowed them to set differences and stress aside, and opened a discussion on the subtle quirks that make us—and how we make our gazpacho—special. It was also laced.

And then there are of course the garnishes, or “tropezones” that translates to “things you would stumble upon.” Toppers can include cubed pepper, cucumber, tomato, hardboiled egg and serrano ham.

From there, consider gazpacho an impeccable canvas for seafood, cooked or canned, even tuna tartare. Serving it as the base of a layered crab or shrimp salad is always a success. Fresh goat, feta and other cheeses can take flavors in a different direction.

Going back a few decades, Spanish chefs like Juan Mari Arzak and Ferran Adrià began a strong creative movement with a fresh look at regional ingredients and seasons. Welcome additions to the classic started appearing on menus.

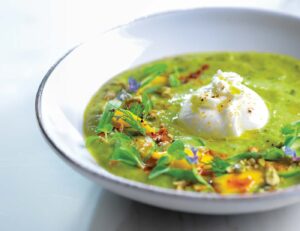

Successful combinations with the tomato base include strawberries, cherries, peaches, watermelon, beets, cantaloupe and raspberries. Leaving the tomato behind, green versions with grapes, peas, avocado and even mango are wonderful. There is also the possibility to experiment with textures, going from silky with a high thread count to roughly chopped.

If there is a recipe that reads like sheet music for jazz improvisation, it is definitively gazpacho. The lines between sweet and savory; soup, salad or sauce; smooth or textured; and even traditional or novel are all meant to be broken.

Draw a new line with what you are and love.

About the author

Analuisa Béjar loves exploring flavor routes as the chef at her Sunny Bakery Cafe in Carmel Valley. She is a recent transplant from Mexico City, where she was a food critic, award-winning writer, editor, recipe developer, culinary teacher and organizer of Latin American gastronomy competitions.

- Analuisa Béjarhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/analuisabejar/

- Analuisa Béjarhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/analuisabejar/

- Analuisa Béjarhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/analuisabejar/

- Analuisa Béjarhttps://www.ediblemontereybay.com/author/analuisabejar/